Psychology of Mistakes

In the Sunflower Foundation’s “Money: critical” debates, a whole range of psychological themes play a role. What’s the point of making money? What’s the point for the counterfeiter to print fake bank notes? What’s the point of pocket money, getting it or giving? Activity, doing something the world of work, plays a large role. And here I want to introduce a theme from industrial and organizational psychology, one that’s interesting for other areas of life, I suspect, the subject of mistakes.

Prof. Dr. Theo Wehner

Work- and Organisational Psychology, ETH Zürich

Mistakes are taboos

“Errare humanum est.” To err is human,” goes possibly the oldest old saying, elevating us above mere animals. Only people can make mistakes in this sense. It’s a human peculiarity.

The mistakes we make in our lives are rarely met with high praise. We tend to cover up our mistakes, belittle them or blame others – do anything to firmly separate ourselves from any responsibility for said mistake. Mistakes are taboo in the working world and in the broader society too. They are without redeeming qualities, as I wanted to suggest in the start.

Error friendliness to be promoted

I’ve been analyzing error-friendly behavior for over thirty years. I’ve pursued this in such a way that can itself be error-friendly. That means that aberrations or missed targets are not seen as catastrophes but rather that aberrations and missed targets are, as the best definition of the word “mistake” puts it, learning opportunities.

Another saying comes to mind in this regard: “You learn from your mistakes.” Or, “Adversity makes us wise.” I’d put it even more pointedly: ´From what other than your mistakes can you learn?” Departures from the plan make learning imperative. Why did I mistake right for left here? Why did I misread this entry and perform the wrong task? These deviations in fact encourage learning.

There’s often something of a gap between the expected goal and the one actually achieved

To speak of mistakes is to speak of missed targets and ill-chosen actions. And when you look closely at mistaken courses of action you see clearly that we humans are no longer guided by reflex and instinct. We have desires and needs, and to the extent we are aware of them, a goal takes shape in our minds. We anticipate goals and try to reach them through our plans and actions. The problem is, there’s often something of a gap between the expected goal and the one actually achieved.

This gap can be modest or large. It can be that I planned to meet friends at three o’clock and I arrive at three-ten. No problem. They’re friends and they will wait. If I want to take a train at five after three and I’m late, then that train leaves without me. The options for correction depend on the schedule.

The gap between the expected and realized goal determines the gravity of the error, its severity and also the options for correcting it.

When we look at just what it is that can be learned from mistakes, and at how to go about this learning, than we realize that mistakes teach us to broaden our expectations. When I’ve made mistakes, I’ve learned to expand my outlook even wider than I had previously. A mistake is always a good trigger for learning and the lessons can be applied to many other areas.

Many artists have grappled with mistakes

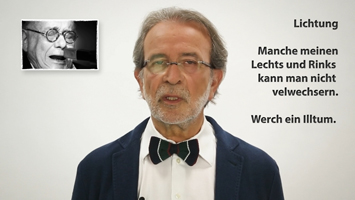

Let’s shift the discussion to art. Many artists have grappled with mistakes. Composer Mauricio Kagel purposefully added “wrong” notes to his works. And in dance, stumbles and even falls are often choreographed into pieces today. The lyricist Ernst Jandl has always fascinated me. He’s difficult to translate but here’s a four-liner from his 1996 book, “Loud and Luise” that I particularly like:

- Glarity

- Some of my

- lights and refts

- cannot be

- defused.

- What a missed ache.

Jandl was well aware that we would understand what he was getting at, but he wanted to lead us deeper into language, into a spoken aesthetic whereby expected sounds are reversed. Thus, what he wrote is a lyric, not an erroneous sentence.